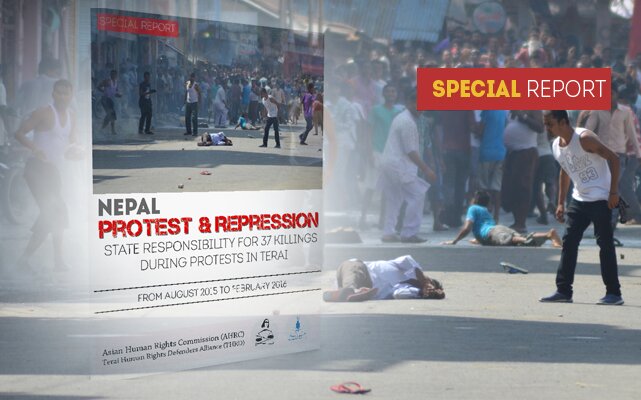

This report assesses the use of force by the Nepal Police (NP) and Armed Police Force (APF) during protests that occurred between August 16, 2015 and February 5, 2016 across the districts of the Terai. The protests occurred largely under the umbrella slogan, “Now or Never”, and challenged the legitimacy of the constitution approved on September 20, 2015. The focus on the use of force is important because it has long been identified as a systemic and institutional problem in Nepal. In spite of exhaustive investigations and detailed recommendations regarding the police excessive use of force during the April 2006 Jana Andolan and later Madeshi Andolan of 2007-08, this report concludes on the basis of credible eyewitness testimony and other documentary evidence that these systemic problems have not been addressed.

The THRD Alliance and Asian Human Rights Commission (AHRC) conclude that the result of this failure was a repetition of longstanding patterns of excessive use of force, resulting in the deaths of 34 protestors and bystanders.

For PDF copy, please click here.

Overall chronology

The Terai protests can be divided into two phases, beginning on August 16, 2015 and then, in a second phase, from September 23, 2015 until 5 February 2016. Protests mainly took place in Tikapur (Kailali), Birgunj (Parsa), Janakpur (Dhanusha), Jaleshwar (Mahottari), Rajbiraj, Bhardaha (Saptari) and Rangel and Dainiya (Morang) districts with most of the protest-related killings occurring in these places.

On August 23, 2015, the Chairperson of the Constitutional Drafting Committee, Krishna Prasad Sitaula, tabled the first draft of the proposed new constitution in the Constituent Assembly (CA), as the Constitution Bill of Nepal. After clause-wise discussion, the CA approved the new text on September 16, and the President promulgated the new constitution on September 20.

On September 23, 2015, as the public demonstrations against the new constitution escalated across the Terai, some protesters began to blockade border entry points with India, marking a second phase. The border blockade ended on February 5, 2016, following increasingly polarized debate nationally and locally about the impact of the blockade and the demands of the protestors.

Twenty-seven out of the protest-related deaths occurred before the border blockade as the government declared one area after the other (including parts of the East-West Highway) to be a zone prohibited from protesters. As the protesters defied those zoning restrictions, the government imposed a series of curfews in these areas. The demonstrators defied the imposition of prohibited areas and curfews, leading to clashes with the NP and APF.

The nature of the protests

Protesters vandalised property of some lawmakers and their relatives in the Terai including the house of the elder brother of senior NC leader, Bimalendra Nidhi, in Janakpur on February 2, 2016.

Most demonstrators viewed the UDMF as the main leading political force during both phases of the protest. While spearheading the movement, however, the UDMF was concerned about the dangers of communal fallout and urged its followers not to do anything that could create communal hatred or communal conflicts in the country. Apart from the killing of three Madhesi men by a mob in Rupandehi in August 2015, the AHRC and THRD Alliance are unaware of the targeting of any other individuals, whether of Madhesi or hill origin. Media reports and public statements by government and civil society actors reveal a protracted failure of dialogue as well as a willingness of some actors to exploit this divide for personal, political and institutional motives.

While the NP and APF were responsible for many human rights violations during the protests, protesters were also responsible for serious violence, including for the killings of police personnel in Kailali and Mahottari districts. On August 24, 2015, eight police personnel, including SSP Laxman Neupane, were brutally killed by the protesters in Kailali. There is a continuing confusion as to who shot dead a 2-year-old child on that day.

On September 11, 2015, APF Sub Inspector Thaman Bahadur Bishwakarma was dragged by a mob from a moving ambulance and brutally killed in a field in Bhagawanpur, Mahottari district.

In total, 59 people may have died directly or indirectly related to the protests. This report only focuses on the killings in the Terai where evidence of state responsibility is incontrovertible.

The killings of police by mob violence attracted national and international condemnation and notoriety and are still the subject of a police investigation. No other incidents of these kinds occurred during the 160 days of protest. THRD Alliance and AHRC investigations indicate that these killings angered and provoked the police personnel in the eastern and central parts of the Terai and became an improper factor in the way force was deployed against protestors.

Use of Force by Nepal Police

The focus of this report is on State responsibility for the use of force, which is governed by the Constitution of Nepal and by applicable international norms. Applying applicable international UN standards of policing to this evidence, the report concludes that in 34 cases there is substantial and convincing evidence that the NP and APF responded with unnecessary and disproportionate force in reaction to stone throwing or other minor levels of violence by protesters.

The basic principle is that lethal force is permissible only in response to a specific and imminent threat to life. While this threat from armed protesters clearly existed in the case of the murdered police officials in Kailali and Mahottari, the THRD Alliance and AHRC investigations found no evidence of this threat in the cases of 34 protesters investigated. In each of these cases, the evidence shows that there were alternatives to the use of lethal force.

The 34 cases of police killings in this report can be divided into three groups: in only 4 cases (11%) those killed challenged the police authority; in 12 cases (33%), those killed were peaceful protesters and in a staggering 18 cases (51%), those killed were not involved in the protests and were mere bystanders or people killed in their houses in the surrounding areas of protests. The three other cases have been included as evidence suggests that the police chose not to protect those killed from a mob attack.

Applicable norms do not permit police to use lethal force in response to an abstractly perceived threat to life: it must be sufficiently specific, identifiable, and imminent. The enormous power given to police is constrained by this principle under Nepal’s Constitutional guarantee of the right to life and by international human rights obligations. To the extent it is institutionalized and officials made accountable, this principle protects civilians from the abuse of power while also empowering police officials to defend and protect civilian life and instill public trust.

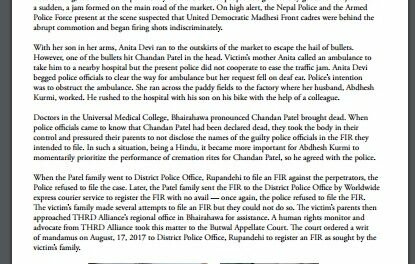

The victims of indiscriminate police firing which killed many bystanders include Ranjana Singh, Binod aka Bindu Kumar Lacaul, Nandani Pandey and 4-year-old Chandan Patel. Those deliberately killed while they were already under police control include 15-year-old Nitu Yadav, Sanjay Chaudhary, Hifajat Miya and Mohammed Sams Tabrez. Police deliberately and summarily killed them while lying injured, hiding in a bush or behind a wall, or running away. Of the 34 protesters killed, 89% were wounded in the head or thorax, contrary to the Local Administration Act, which requires police to aim below the waist.

In addition, in eleven cases, the NP and APF obstructed the efforts of family members and others to transport the victims to hospital (including Rajiv Raut, Raj Kishor Thakur, Nandini Pandey and Dilip Sah).

To date, not one member of the security forces responsible for these serious human rights violations is known to be under investigation, let alone being prosecuted – once again reconfirming the deep-rooted problem of impunity in Nepal. The AHRC and THRD Alliance are also concerned that the NP leadership was not sufficiently capable at an institutional level to anticipate and prevent targeted reprisals by its personnel against members of the Tharu community and protestors more generally. One of the most important lessons learned from this and other incidents of police use of force is the need to ensure that in all cases, lethal force is used solely on the basis of a professional judgment of a specific and imminent threat to life. Police use of force must never be motivated by revenge or other external motives that can only lead to a loss of innocent life and public trust, the demoralization of professional officers and their leadership, and the exacerbation of the risk of violent clashes.

Recommendations to the Government of Nepal

The Government of Nepal has made arrests in the killings of police personnel in Kailali and Mahottari but despite call for probe into the killings in the Terai by the National Human Rights Commission (NHRC) and national and international human rights organisations like Amnesty International, Human Rights Watch, the International Commission of Jurists, AHRC and THRD Alliance, the government has not instituted an independent investigation yet. An end to impunity is necessary to protect human rights and therefore, the government must form a commission without delay to carry out an independent probe into the protests-related killings. The government must also ensure that its actions are not aimed at silencing dissenting voices and needs to ensure that all those arrested are given a fair trial.

The state is liable to investigate all these killings but none of the state organs are taking actions towards that end. Such lack of accountability on the part of the government gives an impression of complete impunity where prosecutions against the powerful and security officials are almost impossible. Had the government formed a commission to independently probe into the killings of 2007 and 2008 Madhes movement and had the perpetrators of rights violations been brought to justice, such serious violation of human rights might not have occurred this time. This means if no action is taken against the perpetrators of recent serious human rights violations, it could only encourage perpetrators to commit more violations of human rights in the future.

Impunity remains rampant in Nepal and there is every possibility that those responsible for these extrajudicial killings will never be brought to justice. It has been 10 years since the CPA was signed and yet nobody – neither any Maoist cadre, nor any security official who may have been responsible for human rights violation during conflict, has been punished for the crime(s) they might have committed. The Supreme Court of Nepal has asked the Government of Nepal to revise the TRC Act but the government has not done so yet. As long as impunity prevails like this, the human rights of all-Nepalese – whatever their background – cannot be guaranteed.