By Praveen Kumar Yadav & Mohan Kumar Karna

On June 21, the Parliamentary State Affairs and Good Governance Committee endorsed the long-awaited citizenship bill. The bill, which is technically an amendment to the Nepal Citizenship Act 2006, had remained stuck since being tabled in Parliament on August 8, 2018. Upon the endorsement, the bill was presented for deliberations to the House of Representatives.

On July 2, the parliament session was prorogued, and the anticipated deliberations could not take place. That means the passage of the citizenship bill has been delayed by at least five to six months–again.

“This turn of events is very sad and disappointing for all of us, and it ensures the continuation of painful days for people without citizenship certificate, even though they are eligible citizens of the country under the new constitution,” said Sabin Shrestha, Executive Director at the Forum for Women, Law and Development (FWLD), an organization working on citizenship rights.

In the 22 months after the bill was tabled, the parliamentary committee held more than 140 meetings, but members of the ruling and opposition parties disagreed over the proposed amendment.

The most contentious issue pertained to naturalized citizenship for foreign women married to Nepali men. But just a little over a week ago, the committee, in a surprising move, unilaterally went with the government’s earlier proposal. Last September, the Ministry of Home Affairs had proposed the requirement of a seven-year threshold for foreign brides seeking to obtain naturalized citizenship. Since then, the Nepal Communist Party (NCP) has maintained a rigid stance on the issue.

“Naturalized citizenship has remained the most debated issue both during the current lawmaking process and during the constitution-making process,” said Dipendra Jha, Chief Attorney for the Province 2 government. Jha, who was a key observer of the constitution-making process, added that the lawmakers back then postponed the resolution of the issue by inserting a provision requiring a federal law for granting naturalized citizenship.

It has been five years since the promulgation of the constitution, but owing to the absence of the federal law on naturalized citizenship, hundreds of thousands of people qualifying for naturalized citizenship have become stateless.

For their part, the main opposition parties — the Nepali Congress and Janata Samajwadi Party — and parliamentarians who represent the Terai, such as Prabhu Shah and Matrika Yadav of the ruling Nepal Communist Party, have been opposing the seven-year provision for naturalized citizenship.

Civil society members have also decried the following controversial provision, which they feel is unfair to the people living in the Terai, where cross-border marriages have been prevalent for a long time:

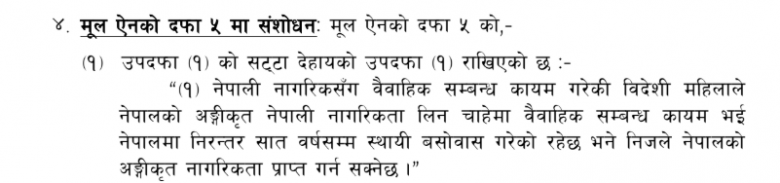

English translation:

Amendment to Section 5 of the Principal Act: The following Sub-Section (1) has been inserted in place of Sub-Section (1)

“(1) A foreign woman married to a Nepali man, if she so wishes, may obtain naturalized citizenship of Nepal if she has continuously lived in Nepal for seven years after her marriage.”

First, this provision clearly discriminates against foreign women who marry Nepali men. The gender-unequal provision cannot be justified on the premise that the constitution has no provision related to the issue. The citizenship bill in its present shape fails to uphold gender equality. The constitutional amendment is required to be gender-equal too.

Second, a law cannot have a provision for a seven-year waiting period unless the constitution has such a provision, according to constitutional lawyers and experts. They argue that once passed, such a law would not just contradict constitutional values but would also be a regressive law.

Third, the constitution has a clear provision regarding the naturalized citizenship of foreign women who marry Nepali men: it says that women willing to get Nepali citizenship will get naturalized citizenship as per the federal law. This means it doesn’t provide for the creation of any residential identity card, the provision that was recently proposed by the parliamentary committee. This attempt to create a parallel identity card is unconstitutional since the federal law, as stipulated in the constitution, needs to ensure citizenship to foreign women who marry Nepali men.

Fourth, the Constitution of Nepal 2015, through Article 289 (1), has already imposed restrictions on citizens by birth and naturalized citizens: they are not eligible to hold the office of President, Vice- President, Prime Minister, Chief Justice, Speaker of the House of Representatives, Chief of State, Chief Minister, Speaker of State Assembly, and Chief of a Security Body. Thus, introducing the new seven-year waiting period in the federal law makes for an unconstitutional intervention.

Fifth, a seven-year waiting period will create practical problems. If a foreign woman who is 33 or older marries a Nepali citizen, she cannot apply for a government job in Nepal. At present, one has to be a citizen of Nepal in order to apply for government jobs. Men and women can apply for civil-service positions only till the age of 35 and 40, respectively.

The introduction of the waiting period demonstrates that the government questions the loyalty of foreign women who marry Nepali men. It makes no sense that a foreign woman married to Nepali man would not be loyal to the country in the first seven years of her marriage and that she would become loyal after seven years. A foreign woman married to a Nepali man changes her surname to her husband’s surname and calls her husband’s and children’s country her own home. Are these not enough to prove her loyalty to the nation?

Nonetheless, the ruling party lawmakers have justified the provision for the seven-year waiting period by saying that there is a similar provision in India. They seem to be ignorant of the fact that Nepali women married to Indian men become eligible, upon marriage, to enjoy almost all the rights that Indian citizens do. Nepali women married to Indian citizens immediately get ration cards, on the basis of which they get their names enrolled on the voter list and get their Aadhar card. They can also get their passports on the basis of these documents, so Nepali women married to Indian men are not barred from enjoying their rights in India.

The main reason for the Nepali state’s unconscionable denial of citizenship to certain people is the ‘nationalist’ psychosis, which stems from the fear that a huge influx of Indians will apparently threaten Nepali sovereignty if citizenship is easily provided. Unfortunately, the newly introduced provision for naturalized citizenship would largely affect the people-to-people relationship in the border areas.

Madhesis have always been viewed as India sympathisers. In his 1975 book Regionalism and National Unity in Nepal, Frederick H Gaige, an American researcher, wrote that regarding the politics of citizenship in Nepal, this attitude has been well documented. According to him, among Nepal’s ruling elites, a nationalism informed by anti-Indian feelings had contributed to regressive provisions in the 1962 Constitution. A similar kind of nationalism hyped by the ruling party led to the regressive citizenship provisions in the new constitution and in the recently endorsed citizenship provisions.

Furthermore, the entrenched patriarchy also colours the issues around citizenship laws here. Nepal is among 26 states whose citizenship laws prevent the granting of citizenship on the basis of a mother’s nationality. This denial of citizenship has made the lives of countless stateless persons exceedingly difficult and robbed them of their dignity.

Nepal is not party to the two United Nations conventions (the 1954 Convention relating to the Status of Stateless Persons and the 1961 Convention on the Reduction of Statelessness) that address the problems of statelessness. The UN conventions are framework laws, but even so Nepal has not signed these two conventions. That, however, should not mean the country can create regressive citizenship laws. It cannot shirk its responsibility of addressing problems related to statelessness. The government must not forget that Nepal is party to the International Covenant on Civil and Political Rights, which guarantees that every person born in a territory shall have the right to obtain the nationality of that nation if he/she is not a citizen of any other country.

Recently, on 30 June, the Nepal Civil Society Network on Citizenship Rights — a loose network of civil society organizations working on various human rights issues, including the problem of statelessness in Nepal — responded to the citizenship bill. The network–which currently consists of more than 50 organizations lobbying for equal citizenship rights–welcomed some of the progress made by the bill but also voiced concern over the bill’s controversial provisions.

According to rights activists, millions of stateless people are pushed to the point of breakdown due to the absence of a proper citizenship law.

“I strongly believe that stateless people must be our main concern and the centre of our discussion and action,” said Deepti Gurung, a member of the network. “This time, they must be given the opportunity to obtain citizenship, or else the state will have failed them terribly.”

In a recent press statement, the network made public its position paper on the bill’s key issues pertaining to citizenship. The Nepali and English versions of the paper are appended below.

The Nepal Civil Society Network on Citizenship Rights’ position paper on the citizenship bill endorsed by the Parliamentary Committee:

(Original Source: https://www.recordnepal.com/category-explainers/unequal-citizens/ )

![[नेपाली अनुवाद] UN Special Rapporteurs’ Communication on NHRC Act Amendment Bill](https://www.thrda.org/wp-content/uploads/2019/07/LOGO2.jpg)