The Citizenship Bill, tabled in the House of Representatives a year ago, remains stuck there, as political parties remain divided on provisions in the bill.

In the new constitution, some provisions on citizenship require a federal law, and there are some provisions that contradict those of the Citizenship Act 2006. Without a revised law governing the regulation of citizenship, it is not clear who has jurisdiction and how people applying for papers — either through birth or naturalisation — are to be treated.

This year alone, hundreds of people have tried — and failed — to get their citizenship papers. The few who can, have taken their cases to the Supreme Court. But in the apex court, there is a confusion that would be comical, if it did not have such terrible effects on people’s lives.

This is what has happened in the last five months:

- On 2 April, the Home Ministry issued a circular ordering all 77 District Administration Offices to issue citizenship certificates to those eligible by virtue of being children of citizens by birth. The distribution of papers, which had been largely stalled since the Bill was tabled, resumed.

- But then on April 8, a single bench of Justice Purushottam Bhandari issued a stay order against the Home Ministry’s instruction until April 16, in response to a writ petition filed by senior advocate Bal Krishna Neupane, who claimed that it was unlawful for the Home Ministry to issue the circular, since the Citizenship Bill was under consideration in Parliament.

- On April 16, after hearing both sides, a division bench of Justice Hari Krishna Karki and Bam Kumar Shrestha upheld the Home Ministry’s instruction.

- On April 26, in response to a writ filed by senior advocate Borna Bahadur Karki, a division bench of Chief Justice Cholendra Shumsher JB Rana and Justice Purushottam Bhandari ordered the government to stop issuing citizenship by descent to children of those whose citizenship papers had been issued in a 1997 citizenship distribution drive. There is some precedent for this, as in 2001, the Supreme Court annulled some 32,000 citizenship certificates distributed by the government in 1997, as they had been granted by a political commission.

- On May 7, in response to previous writs, a joint bench acknowledged that the Supreme Court’s orders are confusing, and determined that the issue had to be settled by a full bench of the court. The same order again halts the issuing of citizenship certificates.

At stake is not just clarity from the Supreme Court in this critical constitutional matter, but the question of how the state treats people. A December 2015 study by the Forum for Women, Law and Development (FLWD) estimated that 5.4 million people in Nepal do not have citizenship certificates — almost a quarter of the country’s population aged 16 and above. FWLD projects that the estimate (5.4 million), might reach 6.7 million by 2021, which would equal 26.14 percent of the total population.

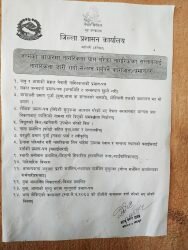

A notice posted on the District Administration Office, Mahottari wall lists 14 different documents/ pieces of evidence required for the issuance of citizenship certificates.

Even when people are able to invest the time and effort and resources to go to the Supreme Court and win, this means little. Arjun Sah of Mahottari successfully sued the government to be eligible for naturalised citizenship. He filed his case against the government in the apex court on February 18, 2013 and the final verdict was delivered on August 21, 2018.

“Three months ago, I submitted the required papers to the Home Ministry following the verdict,” he said. “An official informed me that a meeting will be held to issue the certificate.”

It seems the ministry still is dragging its feet on issuing his papers. “Your citizenship certificate will be issued soon after the enactment of the law,” he added quoting the official.